|

e.nz Professional Engineers magazine, July 2008 Light at the end of the pipe Will one ring rule them all? |

|

|

By Keith Newman The first fibre optic cable was put in the ground in central

Wellington by the old Post Office about 30-years ago offering a ‘huge’

10Mbit/sec capacity. Since then the major carriers have replaced their

backbone networks with fibre, now capable of transporting hundreds of

gigabits of traffic each second. Most cities are connected by fibre but townships and rural areas are still largely dependent on ancient copper cable or wireless solutions. Various private-public partnerships are rising to the challenge and building their own fibre networks that end up being faster and more affordable than anything the mainstream players are prepared to consider. As the two major political parties engage in Gollum-speak ahead of the election, there’s a glimmer of light at the end of the pipedream, promising to free the captives from sub-standard broadband. While National promised to step up with $1.5 billion for open access fibre infrastructure, the government in its 2008 Budget only stumped up for an ‘underwhelming’ $340 million of contestable funding over five years as part of a decade long programme to bolster open access broadband. This would largely be targeted at areas of underinvestment and to build greater international resilience. Another $163 million was set aside for enhancing health, education, research and science and government networks plus $51 million for Digital Strategy initiatives.Government funding is being relied on, in conjunction with other private and private-public cable investment projects, to fill in the rural and urban coverage gaps left by the core carriers, who’ve held the country to ransom with their overpriced underperforming city-based networks. Senior representatives from major telecommunications providers,

utility operators, industry organisations, institutional investors, and

central and local government, are now meeting bi-monthly to sort out

ways to improve the country’s broadband infrastructure. Among the

proposals on the table is InternetNZ president Pete Macaulay’s revised

fibre fund to stimulate public-private infrastructure investment, which

was previously quickly rejected by the Ministry of Economic Development

in 2006. A steady stream of reports, including from the OECD, continue to slam our slackness in getting broadband penetration up to speed. Telecom has been chastised locally and internationally for many years over its failure to reinvest in its network and has shouldered much of the blame for our pitiful performance.We’ve only inched to 19th placing after languishing between 20-22 in the OECD top 30 since 2000. The Government’s goal is to reach the top half by 2010 and the top quarter by 2015, although our hopes of ever achieving that keep slipping as we’re eclipsed by other nations improving their game. While local loop unbundling (LLU) has resulted in a few speedier outposts, allegedly at up to 24Mbit/sec using DSL2, the bulk of New Zealand broadband accounts average 2-3Mbit/sec far short of any government and industry targets. In fact one industry insider describes what we have, as ‘fraudband’. We’re told we need to at least treble current offerings but what’s missing is a grand plan to get us back on track. What the government demands, what Telecom is offering and reports about what the country needs are at variance. The only thing everyone is beginning to agree on is open access, advanced fibre is the only way forward. The first major obstacle to investment is the perception that such

big pipe plans are about lining telco pockets. The fact is

the fibre debate is now considered essential ‘intergenerational

infrastructure’, like building roads, bridges, airports, hydro dams and

other assets that bring broad benefits to the entire nation. What’s fibre for again? Broadband speeds have not kept pace with the demands of technology.

That in itself is a disincentive to multinational companies setting up

in New Zealand, or local companies remaining in heartland townships

where there’s no promise of better service. Meanwhile applications

are more complex, web content is richer, businesses are doing more

online and all the while the files we are creating and sharing are

getting larger. Mukherjee says the myth that residential customers will only use

fibre for watching movies has to be dispelled. "There are people working

from home who are hungry for broadband, people who work in Peter

Jackson’s supply chain and in other industries we don’t even know of,

who are still categorised as residential." He asks, how many of our professional services and creative workers – among the fastest growing employment sectors in New Zealand - actually work from home? "I believe about 30 percent, and in some cities it could be as high as 40 percent. I find it extraordinary and outdated that we evaluate the marketplace simply as commercial and residential." And he’s aware of several applications used in local authority laboratories which cannot be deployed because of bandwidth issues. If its not an availability issue its a cost issue with big pipe tarrifs unable to be justified. For the film industry and many others it’s still a case of modern day ‘sneakernet’, moving larger files around using courier companies. That’s where true broadband can be used to reduce the carbon footprint. "People forget broadband is green. If we had pervasive 100Mbit/sec connections there are things we would do that not only increase productivity but contribute to sustainability. One presentation at the ITU in Kyoto claimed up to 90 percent of Japan’s Co2 commitments under the Kyoto Protocol could be fulfilled using ICT, predominantly broadband, in an aggressive manner." In for the long haul If we’re to deliver 20Mbit/sec or thereabouts to 90 percent of the

population by 2018 at a cost of around $10 billion, the clock is already

ticking and at least half of that will need to be spent over the next

three years. The major cost is not the ‘dark fibre’ itself, the cabling and electronics for nationwide cabling would be far cheaper than replacing Telecom’s legacy copper plant which is in many cases over 60-years old. The major cost is the physical trenching, around $100 - $150 a metre, including the cost of manpower and specialised equipment. Overhead cabling, on telephone poles or alongside power cables for example could save around 25 percent. The dire state of our existing infrastructure and the huge investment needed to get up to speed was clearly identified long before the New Zealand Institute’s series of reports on our broadband needs. Former Telecom chief technology officer Dr Murray Milner, warned in 2006, that New Zealand’s "unbundling" strategy was too reliant on copper. It was likely to cost $1.5 billion to reduce loop lengths from 2km to 800 metres so 90 percent of New Zealanders could get even 5Mbit/sec broadband access. As unbundling was firmed up under the new telecommunications

legislation, many Internet service providers (ISPs) were so distracted

by the opportunity to place their own DSL (digital subscriber line)

equipment in Telecom’s exchanges they overlooked the carrier’s own

fibre-focused plans. Telecom even disclosed the specifics of its cabinetisation plans when it met with wholesale customers in June 2007. It planned to roll out two million metres of fibre to 3600 new roadside cabinets to get closer to the majority of homes by 2010. It currently has fibre to all the major cities and promises to have fibre to all towns with 500 lines or more by 2013. Telecom’s open secret In 2006 Telecom offered to spend hundreds of millions delivering fibre to most towns. It was talking about 20Mbit/sec to about 30 percent of customers and at least 5Mbit/sec to the majority of the population by 2011. However in April last year Telecom chairman Wayne Boyd threatened to spend only one third of the $1.5 billion if operational separation went ahead. The arrival of new chief executive Paul Reynolds quickly bought things back into focus. He raised the bar, promising to deliver 10Mbit/sec to 80 percent of New Zealand homes and up to 20Mbit/sec to 50 percent of homes by 2011. The figure of $1.4 billion was again mentioned. Telecom was simply increasing the promised network speed and

extending the deadline to align with market pressure, regulatory demands

and its own game plan. Its market edge depends on delivering

faster, better managed services to its wholesale clients which include

the bulk of the existing big business, government and rival carriers.

Independent loops

FX Networks cobbled together its own gigabit speed nationwide network through investment and partnership. It owns 500km of the fibre in its backbone; a third of which is leased from New Zealand's railway infrastructure owner Ontrack, and the balance from Kordia and Vector Communications. It offers ultra high speed services through its own ISP, the former CRI-owned Comnet, which it acquired in 2004.FX Networks won the contract for the Government Shared Network (GSN) national backbone and ISP services, and was the first network aggregator for KAREN, managing the complex router configurations required for a core connection into the gigabit-speed academic and research network. It delivers uncapped dedicated speeds of 100Mbit/sec - 20Gbit/sec to strategic top 100 clients and says attractively priced big pipes enable companies to rethink how they operate, including the way run data centres, application hosting, back-up and disaster recovery.I By the end of 2008 FX Networks will have invested a further $40 million extending its private fibre network to provincial centres including Christchurch. It most recently became Internet service provider for TVNZ backing-up and moving data between its operations at up to 1Gbit/sec and ultimately working with the broadcaster on delivering real time content to the home.Powering ahead

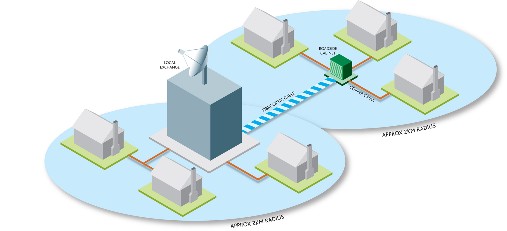

In February it announced plans for a 300km extension between the North Shore, Papakura and Henderson, creating an 800km fibre backbone ring for the Auckland region. The network will connect 40 of Vector’s electricity substations and 41 Telecom exchanges, enabling greater independent reach for delivery of local loop unbundling. It will also give flagship customer Vodafone the ability to enhance its mobile phone and broadband services.

ISP delivers online TV Further questions were raised when Kordia partnered with PIPE International (Australia) to collaborate on a new private trans-Tasman fibre optic cable to increase bandwidth capacity and competition between the two countries. The new cable would go head to head with the Southern Cross cable, part owned by Telecom and itself overdue for a major capacity boost. The decision made sense with Statistics New Zealand noting a 47 percent increase in the number of ISPs claiming high international bandwidth costs had been a barrier to growth over the past two years. This Kordia deal aligned with Communications Minister David Cunliffe’s claim in February that the government may invest in its own undersea cable to help bring costs down. The new cable won’t be operational until at least 2010 Southern loop success The expanded core network means TelstraClear now has 6500km of optical fibre cable, capable of delivering multiple 10Gbit/sec channels or up to 320Gbit/sec on a single strand, from Auckland through to Invercargill. The build over some of the country’s toughest terrain required mole ploughing, open trenching, drilling and thrusting to lay the ducting which mostly followed the railway corridor. To get to its destination however required 15 km of trenching over Crown Range Road (1080 metres) from Wanaka, the highest sealed road in the country and a special 2 metre plough to place cable through the base of the four rivers.TelstraClear has an exclusive arrangement with electricity network distribution company Network Tasman, to access customers in Nelson, Richmond, Motueka and Blenheim areas and in April signed a deal to use Northpower’s fibre optic network which covers much of Whangarei. It plans to enhance its Auckland to Whangarei network before Christmas. The majority of fibre builds are relatively open access but there are

exclusive deals are creating some frustration for carriers wanting to

interconnect and customer’s seeking choice. Telecom and TelstraClear are

already refusing in some case to allow each other access to certain

suburbs or areas where fibre runs all the way to the premises. There are over a dozen independent fibre projects, often partnering with local authorities. Local Government New Zealand and the Ministry of Economic Development have produced best practice guides to try and streamline resource consents and other obstacles than can occur. All utilities involved in earth works may be required to make their trenches and conduits - gas, sewage, electricity or roadworks - available to anyone wanting to blow ‘open’ fibre.There are still major issues relating to ownership and competition to be sorted out and how interconnection with the uber-fibre proposal might play out, in order to ensure everything remains open access from the holes in the ground all the way to the premises.

Both National and Labour have now politicised the fibre roll out, promising to make substantial contributions to accelerate activity. However this has also served to place many existing plans on pause. Who will be eligible for funding? Will there be further subsidies for local authorities, a new infrastructure company or will the cash go straight into the hands of existing providers? Many local authorities waiting for the long awaited phase two of the Government’s MUSH and Broadband Challenge incentives had already given up. For example the Wellington City Council dumped its $40 million plan to invest in open fibre, claiming that w ithout Government subisidies, it no longer made sense.An earlier proposal to extend fibre optics into the suburbs through a stake in open access pioneer CityLink, was abandoned after a curious report from consultants NZIER concluded broadband had been over-hyped as a driver for economic growth. InternetNZ executive Pete Macaulay said he knew of 15 councils that would have applied for a new round of fibre infrastructure funding but even the most recent Digital Strategy discussion document offered only a vague hint of financial assistance. Uncertainty about the investment climate and the Government’s role

aren’t the only obstacles. Our long term failure to train engineers and

IT people, means we are unlikely to meet even current targets. The

worldwide demand for fibre optic deployment skills, along with

Australia’s own multi-billion dollar government-led fibre to the node

roll out means our skills dilemma will soon become blatantly obvious.

Allegedly underpaid contractors have already been striking for higher

pay outside Telecom’s offices, claims its monopoly position is being

used to cap their rates when they could be earning twice as much for

laying fibre across the Tasman. In the interim Telecom, "will gobble up just about every resource there is in the country," for its own roll out, says Milner. Telecom and its partners Downer and Transfield are involved in ‘heavy recruiting’ overseas and have reintroduced apprenticeships and training schemes, adding 600 new people to the industry in the past 18 months. However Telecom admits it’ll still be "a stretch" to find enough people to meet its own fibre requirements. Even next generation fibre, further reducing the cost of laying light-speed cable by boosting speeds over greater distances without the need for more electronics, didn’t get around the skills crisis. Fibre loop ownership Serious competitors will persist in making the most out of the copper

loop; unbundled access is too good an opportunity to walk away from,

even with slimmer margins through Telecom’s cabinetisation. However,

moving fibre closer to the premises raises some serious questions. This is a core issue that could impact heavily on fibre investment. "If Telecom continues to close the loop and own it, then it clearly becomes a natural monopoly and should be treated in the same way as other natural monopolies, with regulation," says Mukherjee. In its final broadband report, the New Zealand Institute proposed Telecom's fixed-line network be rolled into a partially taxpayer funded investment business to build an equal access advanced fibre network. Fibre Co would provide bandwidth at regulated prices and help shift the focus from competing fibre networks to a single open network. That, it said, would require a billion dollars of government money over 10 years.Of course the proposal was scoffed at by Telecom which only months previously, after speculation it might sell its network, confirmed it was definitively in the network ownership business for the long haul. Mark Ratcliffe, CEO of Telecom’s Chorus network division is staunch when asked about the potential for unbundling or wholesaling his fibre. "Why would we look to unbundle something where all the investment is in the future…It would make the business case for investment in the future network look pretty poor if every time you invested in something, everyone else got access to it." Anybody can lay fibre into the premises, but the point of interconnect back into someone else’s network is where it gets tricky, says Ratcliffe. Most inquiries to date are from fibre providers wanting access to Telecom’s exchanges or cabinets for some form of backhaul interconnection rather than service providers wanting to connect users. "I own the fibre network and have no plans to sell dark fibre to anyone including Telecom... We’re not in the fibre wholesaling game that some others are in. We think that would be quite damaging for the investment we’ve made to date." His business is to build commercial services where there’s a market and he’ll lobby hard to stop governments regulating ‘future investment’. "If they’re going to unbundle fibre we’d argue that you need to unbundle everyone’s fibre not just one of the players."’ Can copper cope? Meanwhile, Ratcliffe insists there’s room in every one of Telecom’s cabinets for competitors to place their copper loop access technology. "Half the space has been set aside for competitors other than our wholesale business; although they will have to rework their business case to accommodate smaller DSLAMs, which are cheaper and have less ports." That goes for DSL2 or even VDSL, which Telecom is currently trialling. Ratcliffe insists the copper tails are sufficient to meet current market needs. "In all forms of life we always want more for less…but there are no services I know of that require anything better than 20Mit/sec to operate optimally."

While politicians and potential investors are still going through the return-on-investment vs public good debate, vendors playing in the fibre space are doing their utmost to gear fibre as a mainstream solution. Alcatel-Lucent, Telecom’s key partner, has been prepping the market for many years as has Cisco, and Ericsson recently showcased the capabilities of its fibre to the node and premises gear. It even dared suggest Telecom’s current cabenitisation efforts hosted technology that was little more than an entry-level next generation broadband. Ericsson strategic marketing manager Colin Goodwin said while a robust and pervasive fibre network could bring business and economic advantages to the country, entertainment services such as video on demand and HDTV would help cover the cost of investment. And he warned bottlenecks in the backhaul fibre network were about to get worse and needed serious attention to handle new services and the last yards of copper into the premises would not cope well with the frequencies required to support high resolution video. While shortening the copper loop and moving to VDSL for speeds up to 30Mbit/sec was part of the solution, only fibre to the premises would deliver the 100Mbit/sec required for future offerings. Demand dilemma To date the focus has been on funding and deploying the conduit, rather than content. Even with the longer ‘time horizon’ for investment returns you need ‘killer applications’, consumer or mass market uses that will drive uptake, including triple play bundles such as telephony, video, pay TV and gaming. Murray Milner is concerned not enough thought is being given to the

demand side, including ensuring people can actually afford whatever

might be delivered, and sticky issues such as who owns the rights to

premium programming can be a major impediment to fibre roll out. Meanwhile the government is ramping up its Digital Strategy broadband map, based on existing networks and estimated future demand. It’s now developing a five year projection of demand requirements to help stimulate potential providers. "While this is largely for the public sector, the private sector can learn from this, it also needs to deal with rich media content and the way the Internet will work in New Zealand," says Milner. There’s a strong view the Government should be leading by example in making the most of its own resources to alleviate broadband bottleneck. It has already proved the benefits of having a Government Shared Network and broadband seer Simon Riley believes this model needs to be taken further.Rather than hospitals, local authorities and education facilities

duplicating resources and paying huge sums for wide area or backbone

connectivity they could operate over a single infrastructure. "It’s not

a big step, essentially the lines company could provide open access

anywhere." He claims huge savings and opportunities could be realized with an injection of $3-4 billion - perhaps through posting infrastructure bonds - even if it meant rolling the assets of Kordia into a new company and getting other big players; especially lines companies, to take a minority shareholding. The Government is already investing in broadband through KAREN, GSN and Kordia, and talking about health and education and is in fact the biggest customers of these services but is failing to fully co-ordinate its investment. Riley wonders whether now isn’t a good time to consolidate.

ends

|

|

That

also means beefing up what it can deliver to its own Internet users and

other ISPs so the case for full unbundling looks less impressive to

rivals which it would prefer to have as customers. All of which requires

it to move as rapidly as possible to shorten the copper loop by taking

fibre to the kerb in the most profitable and populous areas so it can

head off, or partner with the growing number of independent

infrastructure companies who are also busy laying fibre.

That

also means beefing up what it can deliver to its own Internet users and

other ISPs so the case for full unbundling looks less impressive to

rivals which it would prefer to have as customers. All of which requires

it to move as rapidly as possible to shorten the copper loop by taking

fibre to the kerb in the most profitable and populous areas so it can

head off, or partner with the growing number of independent

infrastructure companies who are also busy laying fibre.