An on-line resource for those at risk

Editorial

(updated July 2008)

Editorial

(updated July 2008)

Suicide

Facts:

![]() 2005-2006 Suicide statistics (New Zealand)

2005-2006 Suicide statistics (New Zealand)

![]() News

articles (1999- 2008)

News

articles (1999- 2008)

From

2003 SOSAD significantly reduced its monitoring of media coverage.

Suicide horror still rivals

deaths by car accidents

By Keith Newman,

The number of

people who decide to take their own lives in a society is considered a

fair indicator of not only how well that nation treats its people but

also the mental health and social wellbeing of that society.

If this cruel barometer of our psychological and spiritual weather is

too low it indicates a stormy time ahead in an environment that is

obviously placing far too much stress on those who act on impulses to

end their tenure and points to the likelihood that many more are

struggling with those challenges and what they might do about them.

Outdated

statistics, over two years old before they are released to the public,

once again prove how far out of synch New Zealand is when it comes to

dealing with the crisis in youth suicide which has continued to plague

the country for over a decade.

In a country supposedly

providing a high standard of living, education and health services,

something is dreadfully amiss when the number of suicides continue to be

higher than the road toll, the number of people admitted to hospital for

attempting to end their own lives is escalating.

While young

males still fare badly - around three taking their own lives for

every female - there is growing evidence that females are ending their

lives at an increasing rate. And Maori were at growing risk with their

figures of ending their lives higher than their non-Maori counterparts.

|

Killing |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

|

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

|

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

|

2008 |

|

|

|

|

Statistics from Transport New Zealand and the Ministry of Health and SPINZ |

|||

For many decades, the suicide death rate was consistently highest at age 65 years and over but this changed in the late 1980s with a steep increase in youth (15–24 year olds) suicides. The youth suicide death rate peaked at 27.2 per 100,000 people aged 15–24 years in 1995–1997. In 1998 suicide was the second leading cause of death in the 15-24 age group in New Zealand behind motor vehicle smashes. The rate of self inflicted deaths was three times higher for young males than it was for young females.

Among the 97 countries with suicide data reported by the World Health Organization, New Zealand has scored badly this past decade, at times having the second highest reported suicide rates for young men and women in the developed world. The study, Suicide Trends in New Zealand 1983-2003, showed that over the past 20 years an average of at least 350 New Zealanders have died by suicide every year, and around 2000 were admitted to hospital a year for intentional self-harm.

While the latest figures manicured to downplay the problem have associate health minister Jim Anderton, saying the situation has “remained stable” over recent years, the 2005 numbers actually show a slight increase over 2004. They also highlight a disturbing number of Maori ending their own lives and an escalating number of people hospitalised for ‘attempting’ to end their lives.

The two-year old data released in November 2007 for the 2005-2006 year shows the number of Maori ending their lives prematurely has continued to increase at a higher rate than the national average; 17.9 percent as compared to 12 percent. Across the board males in the 15–44 years age group continue to be most at risk. The number of hospitalisations for self harm across all New Zealanders also shows a significant increase, with more young women admitted than males.

Between 2003-2005 a rate of 13.2 people in every 100,000 died by suicide compared to 13.1 deaths per 100,000 people in 2002-2004, a decrease of about 19 percent from the peak of 16.3 deaths per 100,000 in 1996-1998.

Releasing the statistics at the 5th National Suicide Prevention Symposium in Wellington, Anderton said while the number of deaths by suicide had dropped since the peak of the late 1990s there was no room for complacency. “Any suicide remains a serious concern and is a tragedy for family and friends. In 2005, 502 people died by suicide. Those who had particularly high rates were those aged between 15 and 44, along with Mâori and those living in the most deprived areas of New Zealand. Men also had higher rates than women – for every three male suicides there was one female suicide’’. The disparity between Maori and non-Maori deaths had increased over the past nine years. While the number was down for 2005 the overall rate showed a 5.2 percent increase from 2002-2004 to 2003-2005.

In 2006 there were 5400 hospitalisations (151.7 hospitalisations per 100,000 people), a 7.5 percent increase on the previous year when there were 4992 hospitalisations. “What we do know is more females are admitted to hospital for self-harm than males – in 2006 there were two females admitted for every male. Mâori are nearly 1.5 times more likely to be admitted than non-Mâori and those who self-harm tend to be aged between 15 and 24,’’ said Anderton.

Although New Zealand young people continue to have a high rate of suicide internationally, 80 percent of New Zealanders of those who died by suicide in 2002 were aged 25 years or older. This is the reason given for a change in emphasis from 2005, extending New Zealand's youth suicide prevention strategy into an all-ages strategy. This however also made it difficult to continue tracking what was happening to the youth numbers as the figures the 15-24 years age bracket were no longer broken out for comparison. Nor was it easy to compare the number of young people being admitted to hospital for self harm.

In 1996 for

example there were 144 deaths of young people aged 15 to 24 years

attributed to suicide; that 26.6 percent of total suicide deaths, by

people who made up only 15.6 percent of the total population.

That dipped to 138 young people (15-24 years) in 1999 and by 2000 was

down to 92 deaths. Then for 2001 it was announced

New

Zealand had the highest male youth suicide rate and the second highest

female youth suicide rate compared to other OECD countries but the

actually numbers were declared as percentages per head of population

rather than any comparable numbers.

We were told the

total rate of youth suicide increased with 20 deaths per 100,000

population in 2001 compared with 18.1 per 100,000 population in 2000

when New Zealand had the highest male youth suicide and the second

highest female youth suicide rate compared to other OECD countries.

And in terms of self harm the human figures more easily identified with

loss and pain have also begun to disappear into the percentages.

For

example throughout the country 1054 young people between the ages of 15

and 24 years old attempted to end their lives in the 1999-2000 year

(seven more than the previous period). In Auckland alone, 700 young

people attempted to kill themselves in 2000. In recent years those

actual numbers have been reduced to percentages of population in a much

broader age bracket making nonsense of any attempt to maintain a running

understanding of whether things were improving or worsening. No doubt

those figures are available but they’ve been depersonalised and are not

easy to access.

From 2002 an attempt made to make some meaningful

comparison with road deaths. It is suspected by many coroners and those

in authority that in fact many road deaths of youth are in fact suicides

but there’s no way of knowing for certain.

In 2003 there were 460 deaths on the road and a major campaign was

conducted, investing millions of taxpayers dollars on gruesome

television advertisements and related campaigns to reduce this number.

Not all doom and gloom

While it's easy to get emotional, and I truly feel ill every time i

attempt to bring an overview of the subject for this site, there’s also

a need to keep things in context and not over emphasise what obviously

remains a major problem. New Zealand statistics may well be made to look

worse by international comparisons often because many countries do not

accurately report suicides or tweak them for various reasons including

religion and the desire to be seen in a good light by peer nations.

While the statistics have painted an horrific picture of young lives lost, the reality is that most young people neither contemplate or attempt to end their own lives. While the statistics have certainly given us something serous to contemplate about the state of the nation and the kind of environment we are expecting young people to operate in they should not be taken out of context and used to add to the gloom and fear that some of us already struggle with.

Young people most at risk of making a suicide attempt are likely to have developed adjustment problems through depression, alcohol and other drug use disorders, and anti-social behaviour. They may have come from a family environment subject to multiple stresses and difficulties including socio-economic disadvantage, family dysfunction, physical or sexual abuse, and have recently been exposed to significant personal stress such as the loss of emotional support or trouble with the law.

Suicide remains a relatively rare event for New Zealand youth. It is estimated that while 5 to 7 percent of secondary school students may attempt suicide, it usually results in a minor injury. The average secondary school of 1000 students may expect a student death by suicide once every 12.5 years. Most have typically occurred over the age of 25 and the trend has been seen to ‘stabilise’ in recent years.

The Government earmarked $10.3 million for suicide prevention spending between 2005 to 2009 including funding for Lifeline counseling training contracts, Kia Piki support and training, SPINZ – the national suicide prevention information service, research into the causes and costs of suicide, and the Support for Families initiative. A further $6 million is being spent in the same period on the National Depression Initiative.

Other government agencies' such as ACC, Police, Corrections, and Ministries of Youth Development, Education and Social Development, also undertake suicide prevention work within their allocated budgets. Additional services and resources are provided through the mental health services provided by District Health Boards (DHBs).

Should we talk

about it?

In the 80s and early 90s it seemed youth suicide had been swept under

the carpet. Then came an outcry in the media and the subject came to the

forefront of our national conscience. Among the milestones which put the

subject up for public debate and awareness again was the effort made by

the Yellow Ribbon fight for life in June 2002. This fundraiser was for a

programme that had supposedly helped break through wall of silence,

making it easier to talk about this previously taboo subject in our

schools.

However, the government moved swiftly to undermine that important work

in winning confidence among teenagers, teachers and parents by seeking

to bring down the wall of silence again. Where the government had failed

to act with its own programmes it sought to stifle those who have worked

long and hard to bridge the gap.

In June 2006 Napier coroner Warwick Holmes said he wanted to see

restrictions lifted on the reporting of suicide, to help address New

Zealand's "world record rate of self-inflicted deaths". He called for

the changes during a hearing where four out of six deaths he was

reporting on were self-inflicted.

The "hush-hush" approach to reporting suicide is not working, he said. "We hold a world record for the amount of self-inflicted harm done by males between the ages of 15 and 24…We have a genuine problem in New Zealand and the more attention brought to it will help address this problem."

Parliament's justice and electoral select committee rejected calls to lift restrictions on what news media can report after fears were raised by education and mental health officials that publicity about suicide causes copycat deaths. (Read on)

Copycat concerns

The concerns over ‘normalising’ suicide are complex and there are ongoing efforts to behind in some circles to minimise coverage of suicide and hamstring the media and attempts by coroners to draw attention to the growing problems of people taking or attempting to take their own lives. Such concerns were highlighted in February 2007 after two unrelated ‘suicide clusters’ were reported in Wellington area among young men who knew each other, raising concerns about copycat deaths.

A cluster of suspected suicide deaths among male Pacific Islanders in the Wellington region centred on the deaths of several young men who all knew each other. Another apparent cluster, on the Kapiti Coast, left six dead in the last eight months of last year. All were younger than 24.

This prompted the launch of a new Regional Public Health programme has based on the philosophy of "postvention", targeting help at those left to grieve a suicide, including friends and family, who could become more susceptible to taking their own lives. The process includes "mapping" those affected by suicide and who could be at risk, and advising communities on strategies to help those affected.

Regional Suicide Postvention coordinator Barry Taylor said the risk of copycat suicides among those left behind was a recognised phenomenon. The programme was in response to the two suicide "clusters". He said funerals were important for grieving but services could also act as dangerous incentives for young people wanting to attract attention to their own suffering.

Taylor was planning to work with funeral directors and ministers to discuss ways in which services could still honour the dead without romanticising or glorifying a self-inflicted death.

A Kapiti community group dealing with the fallout of the suicide cluster in the area said that after the apparent suicide of a 15-year-old girl in September, details of the death were spread by mobile phone text messages among local teens. By the next morning, graphic but inaccurate details were posted on the Internet. Within three weeks, two 20-year-old Kapiti Coast men had also died in suspected suicides.

The clusters overlap with some of the suspected suicides revealed in The Dominion Post, involving five Wellingtonians aged 13 to 16. In 2005, Levin coroner Phil Comber presided over five suicide inquests at one monthly sitting. The youngest of those who died was 11.

Appalling OECD record

And while they were using outdated figures a United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) report launched just after the ‘cluster’ bomb hit the media bought further shame to our record of keeping our youth safe. It suggested New Zealand's children and teenagers were more likely to die before their 19th birthday than those from any other developed country.

The

UNICEF

report,

Overview of Child Well-being in Rich Countries (February 2007), paints a

grim picture

rating

New Zealand as last out of 25 OECD countries in its record for keeping

children safe, with the third highest child homicide rate for children

aged up to 14.

The country was also bottom of the ranking for deaths from accidents and

injuries per 100,000 under-19-year-olds.

“The fact is that substantiated child abuse cases have more than

doubled since 2000 – from 6000 to 13,000 last year. In addition to

that, Child, Youth and Family expect over 70,000 notifications this

year, up from 28,000 in 1999-00,” said National Party Welfare

spokesperson Judith Collins. “These figures are a disgrace and show New

Zealand up in a dim light…”

NB:

When SOSAD first began advocating for greater resources for suicide

prevention and help for those struggling with depression and thoughts of

self hurt there was very

little information available on-line in New Zealand. While there are now

several sites focused on pointing people in the right direction,

the bulk of information and resources are still research-based with little

direct insight offered to those in need right now. SOSAD tried to

stand in the gap with research information, current data and links to the

most relevant sites. As others are now taking up that role in a more

efficient manner we have refocused as an umbrella site, a jump

off place for the best resources, information and positive inspiration .

SOSAD (http://www.wordworx.co.nz/sosad.html

) lists every ‘help’ organisation phone number along with any

resources which may be of value to those at risk.

Our prime task is now, however, to build an inspirational resource of

quotes, revelations, poetry, articles and even songs in MP3 format that

may bring some interim relief or insight.

*Information gleaned from NZPA, official press releases, NZ Herald press

cuttings plus personal research.

PS:

There is evidence that some types of media coverage of suicide can

increase suicide rates. Responsible media reporting of suicide is

encouraged. For information see Suicide and the Media: The reporting and

portrayal of suicide in the media at

www.moh.govt.nz/suicideprevention.

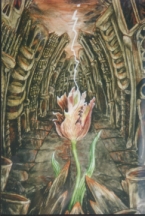

Artwork (C) : Paula Novak, www.paulanovak.com