Ratana

legacy Ratana

legacy

supercedes Labour

How

the man and the movement forced the Treaty back onto the political

agenda

Keith

Newman

(First published in July 2006 by Just Change,

a publication of

Dev-Zone (www.dev-zone.org), an arm of the Development Resource Centre (DRC),

a not-for-profit, non-governmental organisation governed by a charitable

trust.

Without the efforts of Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana and his followers, the

Treaty

of Waitangi may have remained a ‘nullity’, a mere curiosity, rather

than its growing stature today as the birth certificate and founding

document of the nation.

There’s no

question Ratana helped lay the groundwork for the current renaissance of

all things Māori despite the fact a number of modern publications on the

subject of the Treaty of Waitangi do not even mention his name.

Seeing T.W. Ratana languishing between pioneering broadcaster Aunt Daisy

and the original Tuhoe activist Rua Kenana near the bottom of a ‘Top 100

History Makers’ list in November 2005, made me realise how little we

understand his

contribution.

That’s probably not surprising, as nothing substantial has been

published about his life or the movement he founded since 1972 when Jim

McLeod Henderson summarised and re-published his research in the book

Ratana, the Man, the Church, the Political Movement.

Even

Ratana faithful have a hard time getting access to information about the

movement’s history or material that records the words and actions of the

man who was a political visionary and undoubtedly one of Aotearoa New

Zealand’s most powerful faith healers and Māori leaders. Even

Ratana faithful have a hard time getting access to information about the

movement’s history or material that records the words and actions of the

man who was a political visionary and undoubtedly one of Aotearoa New

Zealand’s most powerful faith healers and Māori leaders.

T.W. Ratana set out on a series of nationwide and world tours between

the two world wars, promising to breathe life back into the Treaty of

Waitangi and restore Māori mana.The pan-tribal movement he founded had a

profound impact, rallying the spirits of the dispossessed and scattered

tribes of Māoridom.

"There’s no question Ratana helped lay the ground work

for the current

renaissance of all things Māori."

During a vision in 1918, at his farm between Wanganui and Palmerston

North, he had been told to heal the people and turn Māori away from

their belief in the old gods or atua Māori and urge them unite under one

God (Ihoa), Jehovah of the thousands (the Ture Wairua or the

spiritual law). The second part of his mission was the Ture Tangata

(the physical law), where he gathered signatures for a petition and

evidence about land confiscation to convince the government to make the

Treaty of Waitangi part of the law of the land.

In 1924, Ratana and a party of 40 followers including musicians and

cultural performers paid their own way to England to attend the British

Exhibition and try to gain an audience with British Government officials

and King George V to present the petition which contained the names of

two thirds of all Māori. He had with him a Māori copy of the Treaty

of

Waitangi and sought confirmation from the Crown that it would be

honoured. However everywhere he went, letters from the Aotearoa New

Zealand Government had been sent insisting the group did not represent

Māori.

From

1928, after he had built the Ratana Temple and allowed the Ratana Church

to be established, the prophet and healer said he would divide his body

into four quarters, to win the Māori seats in Parliament. Their main

goal would be to have the Treaty of Waitangi honoured and to improve

conditions for all Māori. In 1932, his first successful candidate,

Eruera Tirikatene, tabled the Ratana petition, which now contained

45,000 signatures and weighed in at 16 pounds (7.25kg). It was

requested that the Treaty of Waitangi be entered into the statute books

in an effort to “preserve the ties of brotherhood between Māori and

Pakeha for all time”.

The petition was ignored for many decades, and even today its requests

have not been completely met.Ratana entered into the legendary

‘alliance’ with the Labour Party (Ngati Kai Mahi) because he saw that

the ideals and goals of Michael Joseph Savage and his ‘Christian

socialism’ aligned with his own goals of raising the bar for the

carpenters, shoemakers and blacksmiths – the ordinary people, of King

Tawhiao’s prophecy. While the Ratana Independent candidates and many of

Ratana’s followers joined Labour, their loyalty remained principally

with Ratana. The relationship was always predicated on Ratana’s 1936

warning to Savage: “May you never forget your responsibilities to the

Māori people, for when you forget this, your government will fall.”

Tirikatene was joined by three other Ratana candidates before the end

of the Second World War. Nga koata e wha were backed and informed by an

enormous network of advisors from across Māoridom. However, after the

death of their greatest advocate Michael Joseph Savage, the Ratana MPs

were regularly sidelined, over-ridden and dismissed in their efforts to

introduce legislation and establish structures that would bring Māori

closer to equality.

The Treaty continued to gather cobwebs until former Ratana youth leader

Matiu Rata eventually pushed through legislation in 1974 recognising

Waitangi Day as a national holiday, and paved the way for the Waitangi

Tribunal to begin investigating breaches of the agreement between the

two peoples in 1976.

Despite the Ratana-Labour alliance eventually pushing through

significant legislation that recognised Māori concerns, Labour’s efforts

to undermine the Ratana ability to ‘block vote’ remained a sore point.

This was evidenced even in recent years through the ‘unconstitutional’

actions of the Labour Party in 1999, which deregistered the 4000-strong

Maramatanga Affiliate despite their fees and membership being up to

date. This effectively shut down the powerful Ratana-based network,

which dated back to the 1930s.

Regardless, politicians still turn up in their droves to Ratana Pa every

January 24th for Ratana’s birthday celebrations. There are many factions

at work seeking to harness the political potential of the Ratana

movement. While Māori Party co-leader Tariana Turia was brought up a

Ratana, and many Ratana are keen to support her and her political

aspirations, Labour continues to hold tenuously to an ancient and much

compromised alliance.

While Ratana is better known for its political heritage, it remains

largely a spiritual movement, strongly influenced

by the original Christian-based kaupapa, and the prophecies and sayings

of its founder. There is a strong undercurrent within the church and

movement to return to its turangawaewae or foundation. Pivotal

among these are the words T.W. Ratana used frequently during his

mission: “In one of my hands is the Bible; in the other the Treaty of

Waitangi. If the spiritual side is attended to, all will be well on the

physical side.”

References

Love, Ralph N. 1977, Policies of frustration: The growth of Ma-ori

politics: The Ratana/Labour era (Masters Thesis), Victoria

University of Wellington

Henderson, J. 1972, Ratana: The man, the

church, the political movement, A. H. & A. W. Reed, Wellington

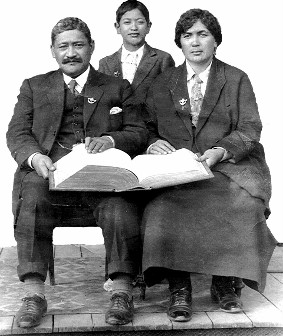

Caption:

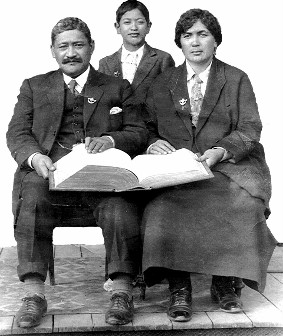

T.W.

Ratana, his wife Urumanao (Te Whaea) and their son Te Omeka with the

large family Bible outside their homestead at Ratana Pa.

Photo: Ratana Archives |

Ratana

legacy

Ratana

legacy